Mary’s Divine No, Advent’s Divine Yes, and My New Tattoo

In a conversation about process theology with a Spent Dandelioner a spell back, it clicked that process holds to a God always active.

This much, actually, I’d managed to grasp for some time, but I hadn’t really ever put it in contrast to more traditional theology, the theology that, short of Pentecost, is generally heard in the Church.

The light went on when I found myself singing the table grace I love so much, and wow, can my family and can the Lutheran family sing this baby in harmony:

Be present at our table, Lord!

Be here and everywhere adored!

These mercies bless and grant that we…

And here, of course, comes a decision that has to be sussed out before the prayer even begins.

Will the collective sing:

May feast in paradise with Thee!

Or will it be:

Be strengthened for Thy service be!

It matters, of course.

The first version is classic low-church piety, a hope that despite and through the trials of life, there will be rest and gladness to meet us at the end.

The second instead recognizes that the food we are about to eat nourishes us for a life of faith, which might, in fact, throw us into and call up a few trials.

Either way, centered in the good Lord and the good singing, we settle in to good food.

But I got to wondering what a different vibe we’d have if the prayer were sung like this:

Be active at our table, Lord!

Be active, Lord.

Move and move us, Lord.

Be a holy verb and form us into holy verbs which act in your holy name.

~~~~~

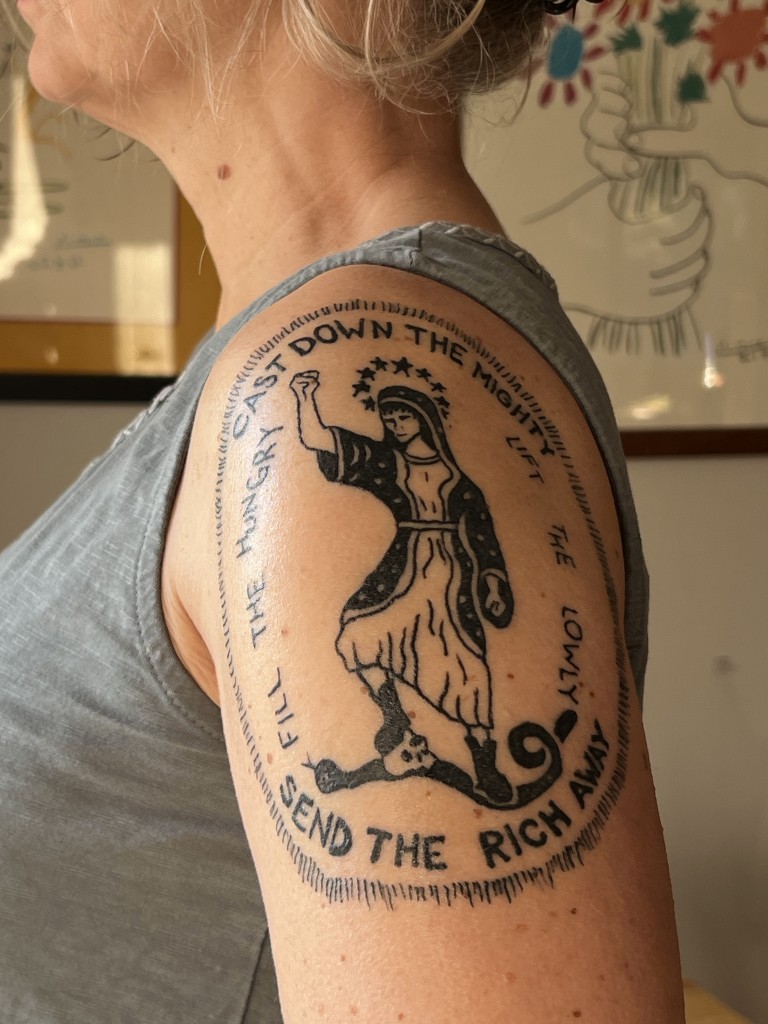

Preparing for Advent, the season of preparation, I got my first tattoo.

It only took a decade or so for me to finally get one, and to figure out why I kept being stirred to get one.

As I’ve fussed with the idea over the years, I’ve loved listening to or reading people’s tattoo story, and why they got them.

Threaded through all the takes was that a tattoo marked externally something that was key internally: an intentional scar that, like all scars, comes with a story.

Perhaps it’s a visual tale of an event, a person, a conviction, a symbol that represented a moment or belief or identity; regardless, tattoos are a perceptible memory and/or reminder for others, but most of all for the person who carries the tattoo.

When I came across the work of Ben Wildflower, and specifically the image here, I almost heard it say, “This one belongs on you,” and I did say, “You know, I think this one belongs on me.”

Strangest thing, actually, and I know it.

But Wildflower’s Magnificat manages to synthesize most everything I hold dear about theology: God’s commitment to those on the margins and who suffer under unjust systems; our call and blessing to be an ambassador of God’s intentions for the world; and the power of women, power which God recognizes even if patriarchy doesn’t.

Seems to me, as a not-very-aside, that if a woman bears God in her belly for 9 months and bears God from her womb in a stable, that she can also bear the Word of God from her mouth in a pulpit.

Anyway.

Wildflower is not just an artist, but a theologian.

I invite you to read up about him and his art here and in the Washington Post here and, regarding his Magnificat, here, and heck for that matter just do a google search for “Wildflower” and “Magnificat” and then get comfy because there’s a lot to discover and absorb.

Elizabeth Johnson, Roman Catholic theologian and Professor Emerita of Fordham University, wrote a reflection on Mary’s song: you can it find online here, and regardless of whether Wildflower himself has ever read it, the gist of her words is in his work.

The Magnificat, Dr. Johnson writes, is deeply, inherently, and necessary political.

Listen—really lean in here—to her:

“Rooted in the biblical heritage of Palestinian Jewish society, this is clearly a revolutionary song of salvation whose concrete social, economic, and political dimensions cannot be blunted. People are hungry because of triple taxes being exacted for Rome, the local government, and the temple. The lowly are being crushed because of the mighty on their thrones in Rome and their deputies in the provinces. Now, with the nearness of the messianic age, a new social order of justice is at hand. Mary’s canticle praises God for the kind of salvation that involves concrete transformations.

People in need in every society hear a blessing in this canticle. The battered woman, the single parent without resources, those without food, the homeless family, the young abandoned to their own devices, the old who are discarded–all who are subjected to social contempt are encompassed in the hope Mary proclaims.”

There are those who say that faith is not to be political.

To them I can say nothing but read the prophets, perhaps chief among them Mary.

She—herself quite possibly enslaved—knew that salvation wasn’t about the bye and bye like pie in the sky.

Mary knew that God had been transformative in the lives of her Jewish ancestors, and she knew that, in the one she was now bearing, God would be salvatory in the lives of her people again.

The form of her hope is concrete, because her life which was in so many ways oppressed was concrete.

Johnson takes it on:

“Here [Mary] takes on as her own the divine no [ital. mine] to what crushes the lowly. She stands up fearlessly and sings out that it will be overturned. No passivity here, but solidarity with divine outrage over the degradation of life and with the divine promise to repair the world. In the process she bursts out of the boundaries of male-defined femininity while still every inch a woman. Singing of her joy in God and God’s victory over oppression, she becomes not a subjugated but a prophetic woman.”

In Mary’s theology—Dr. Johnson has called her a theologian, which I do believe she is—God is not passive, and neither does God believe she herself should be.

God is active.

And so is Mary.

For this reason, take a look at how, and why, Wildflower transforms the Magnificat.

It’s not the past tense—the holy recollection and grounding in Mary’s hymn of God’s history (for you theology nerds out there, God’s Heilsgeschichte) of transformative action—that we see in Luke 1:51-53:

He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.

He has brought down the powerful from their thrones and lifted up the lowly;

he has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty.

In his visual Magnificat, he’s rendered in the imperative:

Cast down the mighty

Send the rich away

Fill the hungry

Lift the lowly

So, yeah.

About that.

Wildflower writes:

“I changed it from the past/passive…which is something I first heard done when we attended St. Marks, Locust St., an Anglo-Catholic church on Epiphany Sunday and the liturgy phrased it as “Cast down the mighty from their thrones. Amen. Lift up the lowly. Amen. Fill the hungry with good things. Amen. Send the rich away empty. Amen.” This really stuck with me as St. Mark’s is in an extremely wealthy neighborhood and attended by lots of folks not lacking in material means. By singing these words there was an admission that the words of Scripture really do call us to economic justice.

This is why I put her fist in the air. There are enough images out there focusing on the lowliness and meekness of Mary. I wanted to make one that highlights her holy rage and her indictment of an economic system built on idolatrous ideas about what kind of people do or don’t deserve things like food and shelter. I like that Mary.”

I like that Mary too.

That Mary indicts me, liberates me, empowers me, connects me, encourages me, sends me.

And now, every morning when I get out of the shower in the morning or get ready for bed at night, that Mary reminds me whose I am, and who I am.

In a sermon preached on the Third Sunday of Advent, December 17, 1933, Dietrich Bonhoeffer spoke of Mary and her song.

He might not have been a process theologian, but he sure understood an active God.

Bonhoeffer preached, “If we want to participate in this Advent and Christmas happening, we cannot simply be like spectators at a theater performance, enjoying all the familiar scenes, but we must ourselves become part of this activity, which is taking place in this ‘changing of all things.’ We must have our part in this drama. The spectator becomes an actor in the play. We cannot withdraw ourselves from it.”

He also proclaimed this: Mary’s song, he said, is the oldest Advent song, and is “at once the most passionate, the wildest, one might even say the most revolutionary Advent hymn ever sung.”

Mary the revolutionary.

That’s a different take on the woman, isn’t it.

As it happens, Advent begins another revolution of the Church year.

Maybe Advent, and maybe Mary, can begin a revolution of our hearts, minds, voices, ways, and priorities, and—as we stare down an election year when come November our democracy, justice, and even basic kindness is on the line—a revolution of our votes so that the mighty, the rich, the hungry, and lowly will each experience a revolution, and also a restoration, of who they are intended to be.

The Divine No to passivity, power, and wealth that oppresses.

The Divine Yes to activity, liberation, and justice.

Welcome to Advent.