Maundy Thursday, the Augsburg Confession, and a Meditation on the Mandates of Faith

The other day, I was looking for one thing, which I did not find.

This is par for the course in my life.

It’s far worse if I need something after I clean: then I really can’t find anything.

Instead, though, I found another thing, something which I needed more than what I was looking for in the first place.

Inside a file drawer, one that is inside a file cabinet which is inside a second-floor closet that is tucked inside a narrow space between the exterior of our house and an underused room, I found a stash of files from my friend and mentor, Walt Bouman.

My jaw dropped, for here in the netherworlds of my house were files that in the netherworlds of my brain I knew I had, but had misplaced, just like I had this treasure trove of knowledge and wisdom.

Two decades ago, Walt and I were working on re-writing what had been The Concordat, which was voted down at a Churchwide Assembly, and for which he’d been a primary architect.

After it failed, but with the hope offered that it could be passed in a new form, I flew from South Dakota, where I was serving as a pastor, to Columbus Ohio, to use my Continuing Ed time to help him take another run at what would later be called Called to Common Mission.

At one point, down in his basement, surrounded by a fortress of file cabinets filled with his research, talks, lectures, letters, and journal contributions, I scolded him (not the first time, nor the last, an occasion which I remember well) because he hadn’t written the books he should have.

“Anna,” he said, his voice squealing a bit as it always did when he was cracking a joke, “I don’t want to write books. But right here and now I give you permission to plagiarize everything here and write your own!”

Well, I have not plagiarized him (though had I, I would have recalled his beloved and oft-thundered “It’s easier to ask for forgiveness than permission!”).

I have written my own book, which could just as well have been his book, given his influence on me.

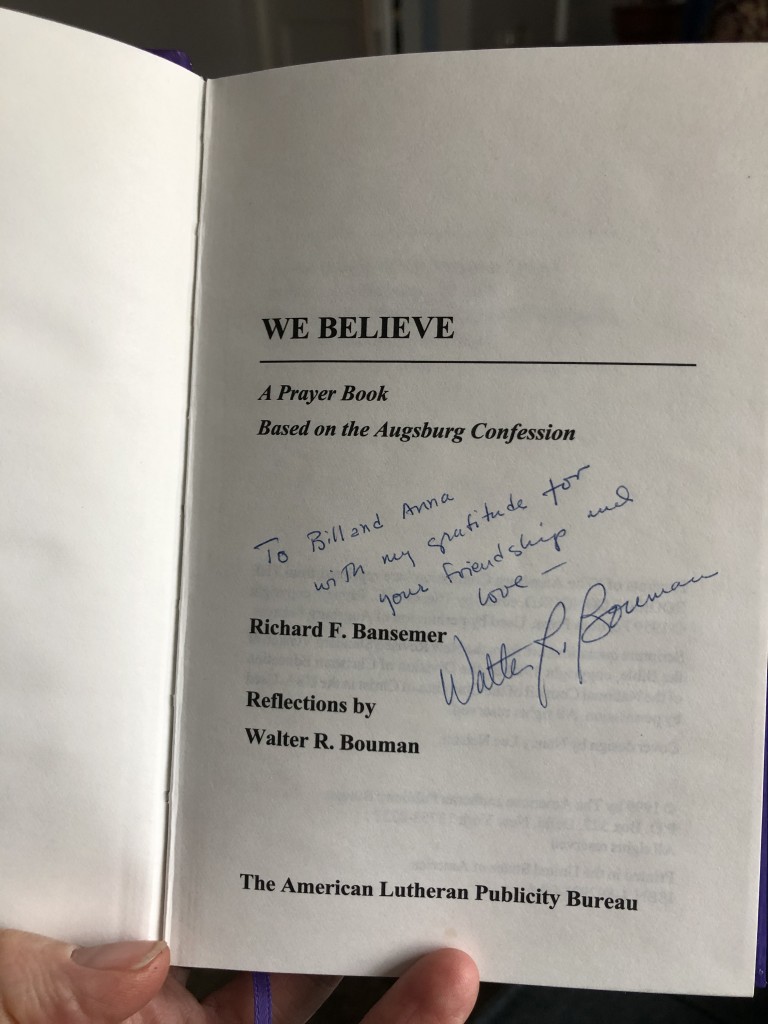

But it turns out, up in my files, I discovered that Walt had, actually, written a book.

I (re)discovered it because of a file marked “Augsburg Confession.”

I’m serving as an adjunct professor at Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary, teaching, wait for it, the Confessions.

So I grabbed the file, plunked my kiester on the floor, and flipped through to see what I could find within that manila file that maybe just maybe would be helpful for my next lecture, which was the next day, which may or may not have needed a bit more work.

There, on the very top, was a letter to Walt, from Pr. Frederick Schumacher, who was then the editor to the American Lutheran Publicity Bureau.

In it, he thanked Walt for his contributions to the work-in-progress Prayer Book, which was using the Augsburg Confession as the basis for the devotional reflections.

Beneath that epistle lay a letter from Walt to Bishop Richard Bansemer, the former bishop of the Virginia Synod. “I have now finished,” said Walt, “what I can do to expand your teaching prayer book on the Augsburg Confession. Let me say, first, that your written prayers are an impressive devotional way of entering into the Augsburg Confession. This is something that Lutheranism has long needed.”

And he was right.

Beneath this letter lay the original manuscript for Walt’s reflections, thoughts spurred by each of the 28 articles of the Augsburg Confession, this foundational document for the Lutheran tradition, this compilation of assertions of what we as Lutheran followers of Christ believe to be essential matters of faith and conviction.

After ~35 mouth-agape minutes, flipping through this gorgeous surprise discovery, my leg was cramping a bit.

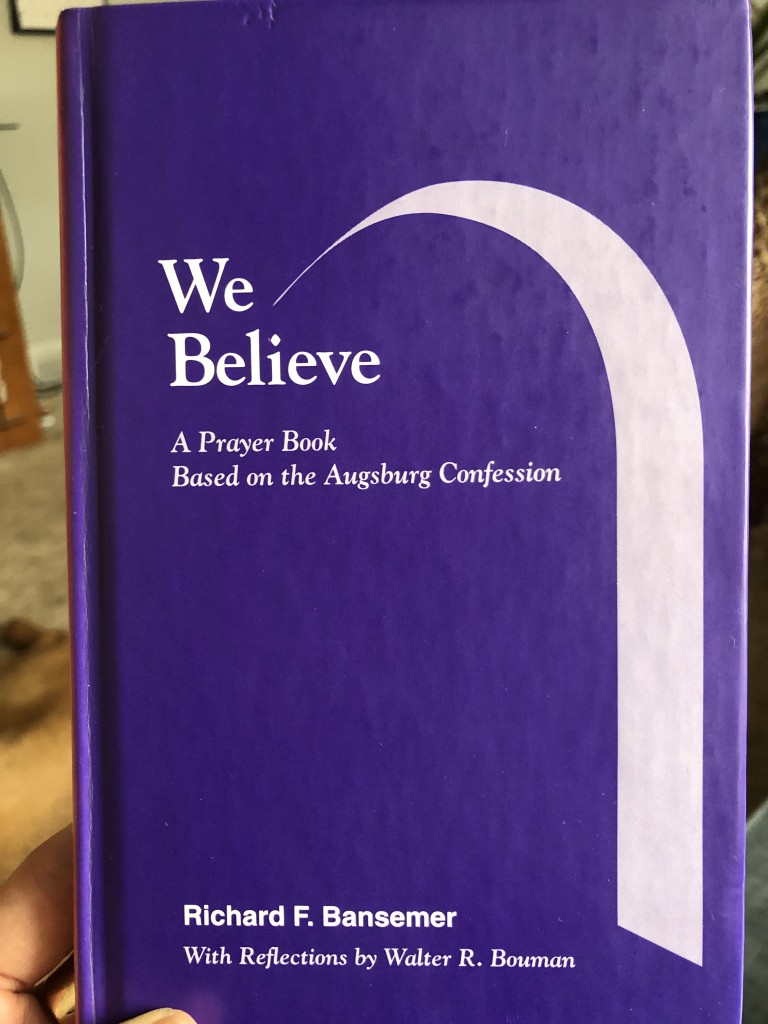

So I got [slowly and with a few muttered expletives] up, and went to my shelves to find the manuscript-become book, right where it had been in front of my eyes for years: We Believe: A Prayer Book Based on the Augsburg Confession.

And with that purple tome in hand, not only was my lecture transformed, but the rest of my afternoon, and the rest of the semester for this class, and much of my thinking about the Confessions from here on out.

~~~~~

We in the Lutheran tradition forget that the Augsburg Confession was, at root, pastoral in nature.

The early reformers were deeply concerned about the well-being of the laity, and how theology done badly could lead to church done badly which could lead to laity being harmed by theology and the church.

So the Augsburg Confession is a document that shows the intersection between theology and faith and the Church and the well-being of the people of God.

The timing of the find was perfect, because as people of God, of what do we have these days more need than some well-being, not to mention comfort at hope?

As the old commercial for Prego said, “It’s in there.”

~~~~~

Today is Maundy Thursday.

The word ‘Maundy’ sounds a bit weird, perhaps because it hits our ears in ways similar to the word “Monday,” which, when set next to “Thursday” simply makes no sense at all.

But the word “Maundy” is etymologically related to the word “Commandment,” or “Mandate.”

In other words, today is a day when we hear two Commandments from Jesus.

I can’t quite help but think that somehow the word “mandate” carries more heft, though, in a way.

So today we got ourselves some mandates from Jesus, some direction about how as followers of Jesus, this is what we do.

This is what we are mandated to do.

It’s not what we have to do.

It’s what we do.

The doing of them defines our being.

And what are those mandates?

Come to the table.

Serve others.

~~~~~

Article 10 of the Augsburg Confession reads, in part, this way:

It is taught among us that the true body and blood of Christ are really present in the Supper of our Lord under the form of bread and wine and are there distributed and received. The contrary doctrine is therefore rejected.

In We Believe, Walt depended on these words for his reflection, along with this passage from 1 Corinthians 11:20-26:

When you come together, it is not really to eat the Lord’s supper. For when the time comes to eat, each of you goes ahead with your own supper, and one goes hungry and another becomes drunk. What! Do you not have homes to eat and drink in? Or do you show contempt for the church of God and humiliate those who have nothing? What should I say to you? Should I commend you? In this matter I do not commend you!

For I received from the Lord what I also handed on to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took a loaf of bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, “This is my body that is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way he took the cup also, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.

With these two texts in mind, Walt began his mulling.

He immediately notices that clearly, the arguments about the nature and purpose of the Eucharist were hardly novel to the time of the Reformers. Even in Corinth, Walt writes, circa 50 C.E., there were anywhere between quibbles and outright dissension about the Table of the Lord.

But then he makes two points.

First, he wrote: “Jesus’ presence as the offered one takes place in a community of believers who receive his offering by offering themselves for each other and for the world.”

In other words, Jesus did not just come for you.

Jesus did come for you, but it’s not all about you.

Jesus came for the people of God, of whom you are, of course, but of whom every other single person is as well.

So as sisters and brothers, as children of God, we give ourselves for each other in the same way as we would for our flesh and blood, not least of all because in partaking of Jesus’ flesh and blood, the rest of humanity is our flesh and blood.

We are bound to one another because we are bound to Christ.

Second, Walt urged us to recall this:

”If we use Christ’s offering of himself as the occasion for not recognizing the needs of others, if we indulge ourselves instead of offering ourselves, then our meal is not the Lord’s Supper. Then we might as well stay home; we are not the church, for the church is the community of people who receive Christ’s offering by offering themselves.”

Our Confessions class has spoken about how our theologies have changed since COVID-19.

Funny how the theoretical becomes quite tangible in times of crisis.

So here’s an instance of just that, on this Maundy Thursday, of how what once meant one thing now means quite another, post Coronavirus.

This year, unlike years past, the line “Then we might as well stay home” rings differently.

Before, I would have read it as an exhortation: we are Church when we come together and commune together, so come together and commune together as often as you can.

And before, that would have made complete sense, so much so that I would have probably passed right over it.

But it is now after Coronavirus has hit.

I have wondered what Walt would have made about some of the very faithful, and very earnest, and very…vigorous…debates about whether it is possible to offer and experience Holy Communion by virtual means, given the Quarantine that has rightfully and righteously put the kibosh on gathered worship.

But I have been never left to wonder what Walt felt about the essential nature of the Eucharist as not just a defining component of gathered worship, nor about his love of the Church.

Thanks to the promises bound to the pro-offering and partaking of the body and blood, the bread and the wine, of Jesus, we are constitutively part of Jesus, and therefore constitutively part of Jesus’ vision for the world.

The Communion of the Saints, separated now for weeks from one another and with no end in sight, we are feeling hungry, we are feeling parched, for bread, for wine, and for a shared meal of celebration, and many of us are itching to get out of home not just of all to get back to the ‘normal’ of things (whatever that will look like, post-Quarantine), but to be able to help all of the neighbors who are desperately needing the real and visible communion of the saints to bring them the gospel, salvation, in tangible form, like medical care, groceries, child care relief, and company, and to bring them hope.

At the very least, we have come to learn all the more about how precious Holy Communion is and Holy Community is, during this time of quarantine.

And I would hope that we perceive that what for us is temporary has been for others a way of life: hungry, parched, and longing for a shared meal and community.

Perhaps we can grasp all the more that we cannot be fed with Jesus and refuse to feed others.

Refusing food withholds life and offers death.

Offering food extends life and refuses death.

We are by our very definition ambassadors of life, and servants of God and to one another.

We can see that perhaps no more clearly when the central moment of our worship is to offer our sisters and brothers a meal and promise that this is, no really, this is for you.

We can see that no more that no more clearly on any day of the Church than on Maundy Thursday.

~~~~~

The Coronavirus is not welcome, on so many levels.

But after any number of experiences of suffering, I have come to believe all the more that Martin Luther was right: we can be absolutely sure of God’s presence where there is suffering and death, for precisely there is where God begins something new.

I am hopeful that out of the suffering and death that we have seen in the wake of Coronavirus, there will be an awareness of our need to repent of the ways that led to its spread, to the inequities that heightened its scourge most of all among the least of these, and to the iniquities which have systematically undervalued those whom we now call (perhaps fleetingly? perhaps permanently?) ‘essential workers,’ those who are paid ~$10.00 an hour to feed your family, tend to your loved ones, and clean up where you or someone may have inadvertently left the virus so that you and they might not die, even if they themselves risk dying to ensure it.

For 10 bucks an hour.

There is a difference between being servants of Christ and being forced into capitalistic servility, that is.

~~~~~

I mentioned above that I remember my very last scold to Walt.

If you listen closely, you can hear it in this sermon of his I’ve linked below.

It was his last sermon, which was therefore basically Walt’s last will and testament, for he preached it while he knew he was dying.

The thing of it is, we are all dying, all the time.

And yet even dying people need to be fed.

Especially dying people need to be served.

Therefore we all need to be fed and served, and to feed and serve.

That’s Maundy Thursday’s message.

It’s Maundy Thursday’s mandate, in fact.

Feed.

Serve.

Be a servant of Jesus.

Serve one another.

(But these days, please do stay home, for even Walt would say, I do believe, that by staying home you can better be Jesus to one another. It’s easier for me to ask eventual forgiveness of him than permission, and it’s not a far stretch from appropriating his thoughts to plagiarizing them, so I figure it’s all good).

~~~~~

Walt’s sermon can be found here in written form, and here in video. I encourage you to watch it and have the manuscript at the ready, for the baptismal font was particularly loud that day, and sometimes you can hear the living water better than the living word.

Peace.