Rosemary Radford Ruether: In Memoriam

I became a pastor because of a vocational call.

I became a theologian because of my father.

I became a feminist theologian, and found a way to remain a Christian, because of Rosemary Radford Ruether.

Last week, Rosemary Radford Ruether died after 85 years of tenacity, brilliance, good humor, righteousness, and chutzpah that changed the Church, changed the way we think about God, changed the way we do theology, and changed lives.

Social media feeds of women friends and colleagues have cascaded with tributes to her influence in their personal and professional worlds.

Despite the breadth and depth of her insight, I sincerely doubt that Dr. Ruether could have had even a smidgen of a sense of the range and the velocity of her impact on the lives of women she would never meet.

This morning, I went to my study and grabbed two of her books from my shelf: Sexism and God-Talk: Toward a Feminist Theology, and New Woman New Earth: Sexist Ideologies and Human Liberation.

I fanned through them both, though I confess it has been some time since I’d had them in my hands.

But it was the first one, Sexism and God-Talk, that made my eyes get wet.

It was published in 1983.

I was yet in high school when I first opened the book, and it felt so rebellious, so beyond the pale of what I’d been taught to be theologically possible, let alone acceptable, that I remember feeling torn between reading it under the cover of night and brazenly spreading it out, spine cracked open for all to see at the nearest busy coffee shop, and even to tempt an exchange with my not-yet-open-to-feminist-theology father (NB: he’s gotten there!).

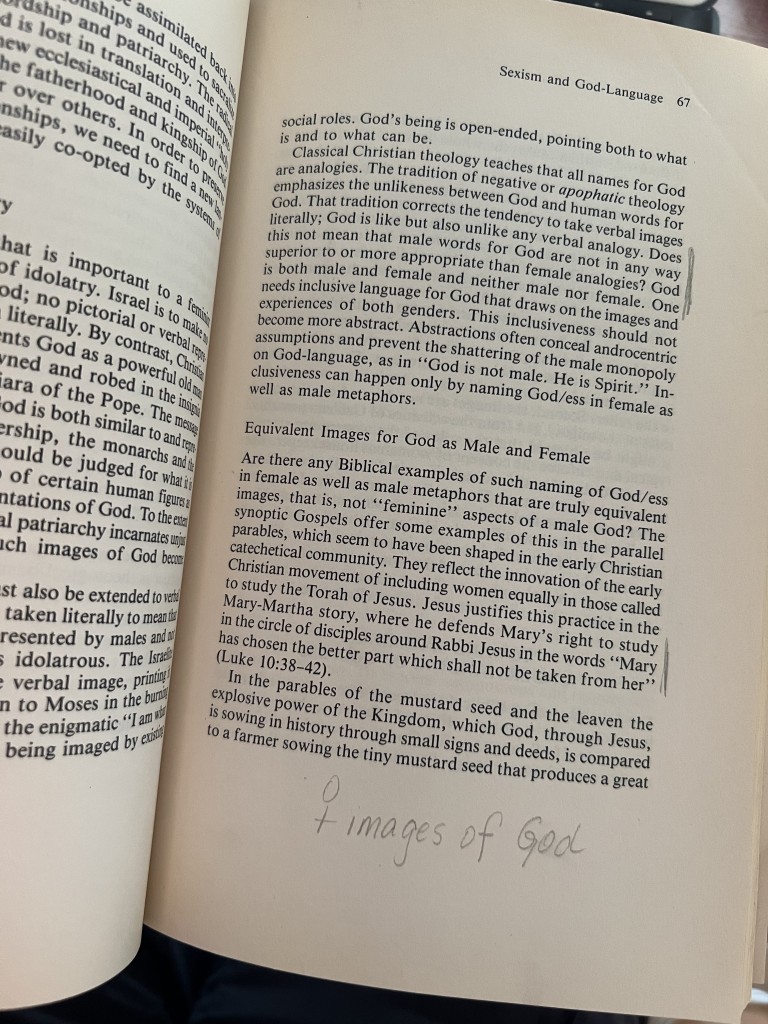

Flipping through the pages, I saw 40-year old underlines, arrows, exclamation points, and dog-eared pages, all signs of a girl blooming in faith and into womanhood, owning her thinking and her theology.

I was positively exhilarated by this radical idea that one could be a Christian and a feminist one at that.

Who. Knew.

And then I saw this:

“ ♀︎ images of God”, I wrote.

Deep. Exhale.

There it was, in print.

She wrote it and I read it.

“God is both male and female and neither male nor female. One needs inclusive language for God that draws on the experiences of both genders…Inclusiveness can happen only by naming God/ess [!!!] in female as well as male metaphors.”

Gobsmacked, I was.

Positively blown back on my kiester to see that a deeply faithful female Christian theologian—a Catholic, no less!—even existed let alone expressed what I’d only had stirrings of hope to see: God was not merely male.

It is not too much to say that this page kept me in the Church.

Her solid scholarship unearthed, blew dust off, shined light on the news that men in power had fashioned a male god with power that suited their needs to maintain power and take away that of women’s, all done in the name of God and therefore with the authority of God to back them up.

Her academic creds, her adept writing, and her relentless courage that was splayed out for all to see by way of her lived convictions opened up imaginations and possibilities and pietistic pursed lips into gaping mouths.

It began to click that if God is not male, then…all of the sexist, misogynist, and patriarchal extrapolations and exploitations emanating from that fundamental premise are rendered bunk.

Complete and utter bunk.

~~~~~

In her chapter on Christology, entitled, “Can a Male Savior Save Women?” Rosemary Radford Ruether wrote, “The Vatican declaration in 1976 against women’s ordination sums up Christological masculinity with the statement that ‘there must be a physical resemblance between the priest and Christ.’ The possession of male genitalia becomes the essential prerequisite for representing Christ, sho is the disclosed of the male God.” (126)

If there had been emojis back then, she would have asked the editor to insert the eye-roll one right into her text.

Implicitly, as here, and explicitly elsewhere throughout her book, Rosemary Radford Ruether also artfully, skillfully, and solidly demonstrates how theology is informed as much by context and culture as it is by any sense of divine revelation.

“The uniqueness,” she writes, “of feminist theology lies not in its use of the criterion of experience but rather in its use of women’s experience, which has been almost entirely shut out of theological reflection in the past. The use of women’s experience in feminist theology, therefore, explodes as a critical force, exposing classical theology, including its codified traditions, as based on male experience rather than on universal human experience. Feminist theology makes the sociology of theological knowledge visible, no longer hidden behind mystifications of objectified divine and universal authority.” (13)

She laid bare the obvious correlation between power structures and values in society with power structures and values in the church, making it abundantly clear (to those who have ears to hear and eyes to see) that what is often asserted as a mark of faith and theological mandate is, rather, a mark of patriarchal quests for self-propelling power.

Page after page, she either undresses the Emperors of Patriarchal Religion, or reveals how they have been, in fact, naked all along.

And she didn’t stop there.

In a day when ‘feminists’ were only beginning to hear their out-calling by womanists, i.e., black women who saw that feminism was a white-women movement driven by and speaking to the experiences only of white women, and when the term “base community” had merely military connotations rather than that of the core liberation theology organic groups burgeoning in Roman Catholic Latin America, Rosemary Radford Ruether put on her socio-economic justice hat.

Feminism sounded good but she nailed it when she named it: feminism really referred to white women’s liberation, and only to white women’s liberation.

“Women,” she said, “always occupy two interlocking kinds of social status. As a gender, all women are marginalized and subjugated relative to males. But as members of class and race hierarchies, women occupy class levels comparable to, although as secondary members of, their class and race. Any strategy of women’s liberation must recognize the interface and contradictions between these two ways of determining women’s social status…White middle-class women are tempted to compensate for gender discrimination but using women of the lower class to do their ‘women’s’ work, thereby freeing themselves to compete as equals with men of their group…The glitter of feminist ‘equality,’ as displayed in Cosmopolitan and Ms., both eludes and insults the majority of women who recognize that its ‘promise’ is not for them.” (222).

She wasn’t an armchair theologian and had no interest in armchair Christians.

One’s faith claims claim one’s faith and life.

She refused to let anyone fail to see that connection, or fail to live out that connection.

For this reason too, Rosemary Radford Reuther was adamantly pro-Choice.

”Male power over women means a denial of women’s right to control their own bodies. Denial of reproductive decision making is fundamental to this control. The male who ‘owns’ a woman is assumed to have total sexual access to her. She must not reject his advances or make decisions about the effects of his ‘seed’ upon her body and her life.” (175)

The woman knew how to wield words, wisdom, and cold hard truth.

~~~~~

But while her book is focused on uncovering both the ruse of male dominant religion and, arguably more importantly, the rich but hidden and suppressed tradition of women and the feminine represented and shaping religious history, tradition, and revelation, there was a deeply pastoral purpose to it too.

Rosemary Radford Ruether knew that when women, and men of integrity, discovered the way in which women have been systematically sidelined in the name of God, they could feel powerful disillusionment with the Church.

She wrote, “It is precisely when feminists discover the congruence between the Gospel and liberation from sexism that they also experience their greatest alienation from existing churches. The discovery of alternative possibilities for identity and the increasing conviction that an alternative is a more authentic understanding of the Gospel make all the more painful and insulting the reality of most historical churches. these churches continue to ratify, by their language, institutional structures, and social commitments, the opposite message. The more one becomes a feminist the more difficult it becomes to go to church.” (191-192).

And wow, back in the day did she strike a chord with me right there.

One foot and half of the other one were out of the door when Sexism and God-Talk talked to me.

And she talked me down and talked me into the Church again, precisely because she was there.

Rosemary Radford Ruether modeled feminist faith, mentored feminist theology, and made it possible for countless women to stay in the church, and even serve in it, in spite, and to spite, its white and patriarchal heritage.

Well done, good and faithful servant.

Rest well, servant of God/ess.

I give deep thanks to and for you.

NPR’s obituary for Rosemary Radford Ruether

National Catholic Reporter’s Biography of Rosemary Radford Ruether

National Catholic Reporter’s Obituary of Rosemary Radford Ruether

Excerpt about Rosemary Radford Ruether in Patricial Miller’s Good Catholics

Rosemary Radford Ruether’s summation of why she was pro-choice

All page references come from Sexism and God-Talk: Toward a Feminist Theology (Boston: Beacon Press, 1983).

~~~~~

In personal news, my latest book Joyful Defiance: Death Does Not Win The Day, published by Fortress Press, is now out!

And, of course, don’t hold back from picking up my last book, I Can Do No Other: The Church’s New Here We Stand Moment, also by Fortress Press.