Jøtuls and Bowls of Coals on Heads

I have a new Jøtul F 118 Black Bear Stove.

It makes me fairly gleeful.

The thing is tiny, but jeepers is it powerful. Heats the whole blame house.

This is a good thing, as the blizzard that is sweeping across the upper midwest has just in the last few hours announced its arrival here in Two Harbors.

Co. Zy.

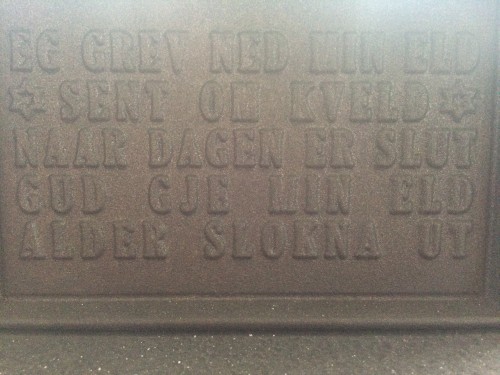

And don’t miss the plate with the imprinted Norwegian proverb! På engelsk, it says:

I built me a flame

late one night

God will my flame

never die out

Some websites with a sense of humor have posted that they were disappointed to actually learn the translation. They thought it was Norsk for “Warranty void if over-fired.”

Grin.

But nope: it turns out to be a poem of hope in the promise of warmth and God’s undying presence.

This marvelous wood stove makes our whole house feel like that, especially as snow and below-zero temps bear down: a poem of hope in the promise of warmth and God’s undying presence.

My lovely Black Bear is famous for something called the cigar burn principle: the fire burns from the front of the stove to the back, and just a couple of logs last for 5-8 hours. A long, slow burn keeps our home toasty for far longer than this tiny little black rectangle would make you guess.

So when the thing is ready to be stoked again, I open up the door, reach into the back with a long-handled shovel where the hottest embers are (that nasty burn on my wrist reminds me that I really need long-sleeved fire gloves…and way more coordination), and I scrape them toward the front. With them, I whip up my next batch of kindling and fire.

I can tell you with sinful pride that I haven’t had to relight my Jøtul for over a week, because the stove keeps the coals so very hot. Just place a few cedar siding cast-off chunks (donated to our family’s cause from my friends the Cedar Coffee Company: thank you again, good people), a bit of newspaper, and my breath blown on the red-yellow embers lights the coals in a flash.

It’s unreasonable how much satisfaction I get from that fact.

For the last few nights, though, after I had gone through the ritual of re-lighting the fire with the embers and my breath, I’ve had reason to sit in front of my stove for a long spell.

As is often the case with Scripture, when you have an experience that directly connects to a certain text, the words and import become all the more real.

For example, my father led and participated in some archaeological digs over in Israel, back in the day. I grew up, then, with a variety of oil lamps from different eras. Holding these tiny clay pots, with evidence of ash where the wicks were laid into the oil, makes the references to them in the Bible all the more powerful: You realize that “Keep your oil lamps lit” is a lot harder than you think, because it meant you had to be constantly vigilant, since they were sometimes smaller than the palm of your hand, and didn’t hold much oil to being with.

So thanks to my Jøtul and some matters in my world, here’s the image that has come to my mind in the last nights: the one of heaping coals on an enemy’s head.

You can find it in Psalm 140:

6 I say to the Lord, “You are my God; give ear, O Lord, to the voice of my supplications.” 7 O Lord, my Lord, my strong deliverer, you have covered my head in the day of battle. 8 Do not grant, O Lord, the desires of the wicked; do not further their evil plot. -Selah- 9 Those who surround me lift up their heads; let the mischief of their lips overwhelm them! 10 Let burning coals fall on them! Let them be flung into pits, no more to rise! 11 Do not let the slanderer be established int he land; let evil speedily hunt down the violent.

And in Proverbs 25:

20 Like vinegar on a wound is one who sings songs to a heavy heart. Like a moth in clothing or a worm in wood, sorrow gnaws at the human heart. 21 If your enemies are hungry, give them bread to eat; and if they are thirsty, give them water to drink; 22 for you will heap coals of fire on their heads, and the Lord will reward you.

That particular text caught the Jewish attention of the Apostle Paul, who repeated it in Romans 12:

19 Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengenance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord.’ 20 No, ‘if your enemies are hungry, feed them; if they are thirsty, give them something to drink; for by doing this you will heap burning coals on their heads.’ 21 Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.

Turns out, the more I did some poking around, that scholars aren’t always so sure about what the phrase can mean: cases can be made for and against any and all of them.

But a quick run-down:

1) Our quick tendency to want retribution, judgment, and lasting pain on one who harms us has many people of faith gravitating to the image of fire as one of lasting punishment: eternal hellfire and brimstone, and all of that.

I get it.

As I may or may not have said on this blog before, generally gentle person though I (think I) am, I confess to finding some small comfort in imagining where, were I of Dante’s ilk and theological persuasion, would I stick someone who really, really ticked me off? What fitting punishment would be rendered for their wrong?

And then I feel bad and go back to working on forgiveness…while, perhaps, returning to the image now and again if necessary.

But in point of fact, many scholars believe that the image of fire is embedded in the refiners’ vocation: it is a purifying fire, a fire that destroys that which is impure, and which not only retains, but cleanses and perfects and beautifies that which is left behind.

That is, the point of fire and brimstone is to condemn the evil and restore the good.

For good reason, we tend to avoid getting burned. In fact, those who are immune to feeling pain are in real danger of harming themselves, and even others, because they cannot perceive when the fire is hot.

They and others get burned anyway, of course.

But if you are into refining, you know that a hot fire is exactly what you need to make your creation stunning.

What is left is quite, quite breathtaking…as was, to be sure, the breath-taking process that was necessary to get there.

So, in short, as far as the text from the Psalm, one can read it as vengeful wrath, and have good reason to do so.

I prefer to read it is a righteous wrath, as referring to a blaze of fire that does not miss impurities, but rather is stoked precisely for them, the hot blaze leaving the created thing as it was obscured from being, and as it was meant to be.

2) Seems as if the Proverbs text takes a different slant on it; or, depending on the scholar, a couple of different slants.

The first way of considering it is the most obvious. If someone has been a complete and reckless idiot, call the person back by kindness. Shower them with love, and gentleness, and mercy. They will be called back to the right path by way of example and by way of shame.

The hope is that when others love the wounder through and despite their obnoxious harm, ideally, the kind acts will recall them to their better selves.

It’s always struck me as potentially passive aggressive, manipulative, bordering on cheap grace, and dangerous, particularly when the onus of responsibility for healing is put on the one who is already, by definition, in one or more ways vulnerable.

But I see the point, and can see, depending on the circumstance, value to the method of seeking healing and reconciliation.

The second piece is interesting to me. According to a variety of sources I found, in some parts of the ancient near east, if a person were foolish enough, distracted enough, apathetic enough, to forget to keep their own coals burning, so that their fires would go out, they would be forced to go to a neighbor for help. They’d have to admit that they had been negligent to tending their own flames, and needed assistance to get their stoves relit. Without other people intervening, even when inconvenient to them, the person would (admittedly by their own fault) be hungry and cold.

So the neighbor would offer not only coals, but would put the coals in a bowl fashioned precisely to fit on the tops of a head, and place it on the head of the impossible neighbor so that she or he would have a shot at rewarming their fire.

As any person of faith knows, even if by the neighbor’s own idiotic doing, his or her own cluelessness and/or carelessness and or complicity in the crisis, no one should ever be left out in the cold without getting help to again find and maintain the fire necessary to live.

————–

As I have sat in front of my fire these last several nights, and now on this blizzarding day, and mulled these texts and mulled matters in life, it seems like the best interpretation isn’t an either/or, but an all-of-the-above.

Burning coals singe.

I know.

And as far as Scripture is concerned, the over-arching message is that God is committed to exactly what my Jøtul is: that our flames never die out. God has dedicated Godself to restoration, to mercy, and to grace.

But that does not mean that God doesn’t get righteously pissed, nor that we don’t whip up reasons for God to be so…some of us more than others.

So there is also a consistent tradition in the texts of God’s wrath when we harm others.

The wrath is real, and God’s anger is hot, and righteously so.

But it never burns our essence.

Our essence, I am convinced, even when all and everyone else says otherwise, our essence is good, and is breath-takingly beautiful when restored, and is worthy of being refined.

That is the intention of God’s burning fire: to burn away our harmful impurities, and to rediscover what has been hidden by them.

I think also that there is something to be said for offering kindness to people who do harmful things. When safe, and when there is some confidence that a hurt will be acknowledged, the approach can indeed be redeeming and healing.

But that last piece, that bit about putting coals in a bowl on the head of someone who let their coals run out, that one has intrigued me most.

That one is an image both of someone who had taken for granted that their fire would always burn, but who discovered, when suddenly quite, quite cold, that they were wrong.

They need help.

They can’t relight their fire, for they not only have no embers: they have no, or very little, breath.

So, as I stare at my Jøtul, and I realize that my embers are many, and they are hot, and that I have breath and wood to keep it going, I am aware of those who have none of those things.

And I am aware that they are cold, and their rooms might be dark, even if by their own idiocy.

In addition to being called out as need be, they equally need help, and they need kindness, and they need breath.

Come to think of it, a really large bowl of crazy hot coals placed on their head, and a poem of hope in the promise of warmth and God’s undying presence, might be what they need more than anything.

Delight to read!

My wife and I met on a dig in 1972, in Upper Galilee, near Rabbi Shamai’s tomb.

That’s a terrific story…and probably not one that many can top.

How relevant and needed. Thank You!

Thank YOU, Cheryl!

Such wonderful stuff, and a such a challenge to enact. Thinking on this on my still Saturday morning.

Thank you, James. Peace to you on this still morning, even though hearts and spirits may be restless!

Grateful for your abundant and hot embers. Happy Thanksgiving to you and yours, dear.

Likewise, good man. And next time you are in the area, don’t you dare drive on by our spot!

Isaiah 6

We are not experiencing weather as severe as you but the temperature has dropped 30º and the wind is blowing and there is some snow flakes and our potbelly stuff is keeping us beyond sufficiently warm. I have to admit that by April I find it a nuisance (understatement) but this night it is all about joy and gratitude and warmth. Thank you for your thoughtfulness and inspiration and get some gloves!